1. Start with some essential viewing

There are a raft of great photographers working today who, together with past masters, could offer you the tools to develop your photography. It’s actually a bit of a minefield, so for the purposes of this plan, I’m going to focus on one who deserves your attention: Harry Callahan.

His most fertile period, working in black and white, was between the late 1940s through to the 1960s. Callahan shows us how to frame the everyday and ordinary in a transformative way. During his life’s work he dipped into street photography, still life, landscape, nudes, architecture and experimental imagery, each time considering composition and tone to reveal abstractions.

His influence can be seen throughout contemporary photography. Observe how he uses light and shadow to simplify a scene or direct the viewers eye around the frame using contrast. You may not work in black and white yourself, but after viewing his images, you’ll want to.

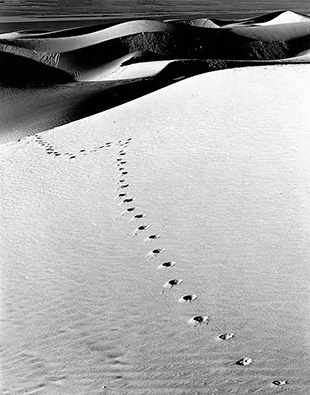

My own photo taken some 40 years after viewing Callahan’s work. His influence runs deep. (Photo by Darren Lewey)

2. Acknowledge your visual drivers

From childhood, the places we experience that seem to offer us a pleasant connection become more important to us. With busy lives built around routine, work, commuting and family commitments, we can lose touch with how visiting these locations can make us feel. We didn’t realize what they meant at the time, and don’t realize the usefulness of them now.

These places are visual drivers for your photography. You can use these places to kickstart a new photographic direction, to branch into project or themed work. You’ll be more connected and more engaged, and your photographs will reflect this. So find those places again and begin exploring.

3. Identify the frame before framing

What’s my interest in taking a certain photograph? When working with workshop participants, I will often observe them pointing at a scene that appears to offer no more than a record. When probed, they’re not sure what they are looking at, or they have an intention but it’s intellectually fuzzy.

Instead, think about what the essence of the scene is you want to photograph. Articulate its component parts out aloud in your head, and include both foreground and background subjects as part of your reasoning. Develop a parrot as your alter ego, always asking why it is you want to photograph this scene.

Rock formations can be a great place to find form. (Photo by Darren Lewey)

4. Forget the idea

Think of an idea, mull it over and then forget it once you’ve arrived on location. Whichever concepts you have in advance about a subject or story are an intellectual wish list. Regardless of how much you think it through, what visually transpires will be quite different from what you set out to find. A football coach’s tactical plan will work only insofar as the other team allows it to happen.

A successful concept or project formed away from the field will evolve and develop once up and running, so the ability to improvise and respond to the unexpected is what will make your work more meaningful for you, and therefore more interesting for others. The idea was just the reason for you to start taking photographs.

5. Hook and humanity

Good photos have a hook, visually or emotionally connecting the viewer to a time, place or psychological state that relates to their own experiences. For a series, think about colour and a specific light source. It could be sunset light reflected on a person or space, the northern light through a window on a face, the grey muted colours of a winter’s day or a warm summertime light on a hedgerow. Introduce someone as the subject or their possessions as the object of your framing. How does that create a more emotional response? You should also limit the number of colours in your composition, so think about what they’re wearing in relation to the background and limit the total number of colours in the frame to three.

Natural lighting used to suggest both lives and minds lived inside. (Photo by Darren Lewey)

6. Create your own stories

It’s not the photo, it’s you. The world’s best photographers become so because they create and develop their own stories through experiences, attitude and observation. They’ve dug down a little to raise these to the surface. You can start with what marks out your own life; a route to work, a hobby, favourite haunts or issue based interests. What’s the thread that passes through all of these? Once you’ve found that, then you can locate more subjects that tag along.

The next time you find yourself in an unfamiliar place with your camera or phone taking photos, ask yourself: What’s my connection? Once you know that, you’ll realise how to approach photographing it.

7. Change your hat

It takes time, years to build up a style all your own. That’s what they say. But a style may only be important to a commercial photographer who needs to mark out a turf. For you or I, the motive is to create the best imagery that expresses our view and our story and brings with it the greatest sense of achievement for us. Being non-professional allows freedom to avoid the ruts and forge a new direction for ourselves.

So when you next feel like you’re on autopilot with the same compositional approach, the same locations, the same aspect ratio—then change. Try a different medium, shoot film, switch to a new focal length, try photographing outside your comfort zone, become a different photographer. In short. change your hat.

A first photo made using infrared film. (Photo by Darren Lewey)

8. Begin a project

Over more than 35 years of teaching, I’ve been embedding the use of collections and themes for developing students’ and course attendees’ work. Working this way takes the pressure off looking for the one outstanding winning shot and instead shifts the emphasis to revealing many facets of a location or objective.

Moreover, focusing on a theme allows them to delve deeper into a way of seeing, and in time reveals their own unique way of doing so. Consistency in framing reinforces that understanding, but a project also allows space to approach subjects in different ways. So once you have a theme, call it a project.

9. Get intimate

Within the established photographic community, details offer as much value as big views. It takes a developed eye to notice and shape imagery from what’s beneath us, as much as creating harmony and balance in a wide vista scene. Often as emerging photographers we don’t give the smaller areas enough time, because the presence of a new place is so overwhelming and visually exciting that we want to catch it all.

Instead, slow down and give yourself time to look around you. Home in on subjects that catch your eye and, using a telephoto lens, see if you can make sense of these changes through your viewfinder. Telephoto lenses are a great way of entering the intimate world. Compression of space offers a disconnection from scale and context, abstracting the subject.

Reflected light off the surrounding landscape brings to life this intimate scene. (Photo by Darren Lewey)

10. Scale down the shouty

The photographic online world is saturated with colour, too much from the obvious places: seascapes at sunset or a car in Cuba. Of course heightened colour draws our attention, but replicating it in the same well-known locations will leave your photography being associated with the online tribe rather than the photographic community. If strong colours are your thing, then think about these three approaches:

- Look for the more ordinary, everyday locations to show bold colours;

- At sunset or sunrise, when warm light is dominant, frame instead on what the light falls upon rather than where it is;

- Think about subject colour. Is it an almost exact match to the colour cast from the sun or a complementary colour.

Check out William Eggleston, who uses colour in all three ways.

A reduced colour palette and early light help to create feeling in this image. (Photo by Darren Lewey)

11. Get in competition with a master

The greats are there as an inspiration to show us what’s possible. You’ve seen Callahan and you’ll no doubt have your own to draw on. Artists have always inspired each other and the evolutional wheel of photographic practice reflects imagery in part gathered from others. You will never be Ansel Adams or Sebastião Salgado, as your circumstances are unique to you, but if they were to look at your images, what would they like about them? Would you spark their interest, as their own visual sense is in part reflected back, but through your own unique story?

Pick out some of your best photos and make a shortlist as to what is great about them. Then do the same with your chosen master. How do they match up? Use the master’s as your competitor’s. You’re not looking to recreate their photos, but you would like them to acknowledge the good in yours.

12. Define what beauty means for you

If we look closely at the history of art and photography, we can see that beauty in subject is as varied as there are approaches to conventional forms of beauty. Perhaps the harmonious, minimalist flow found in wild natural places floats your boat; or, conversely, the everyday and discarded, such as flowers found in a graveyard bin, which you can find in Al Brydon’s portfolio. Beauty can be unearthed in the most unlikely places; we don’t need to visit a hotspot. If you recall the scene from American Beauty, in which the main characters watch a plastic bag swirl in the wind, you’ll know what I mean.

Photography has for some time embraced the everyday and casual, but our cultural identities, to varying degrees, are shaped by a desire to be flawless. Beauty in photographic imagery taps into our idealistic belief system. If you pursue the everyday route, you’ll need to look especially intently at your subject, to elevate its spirit and show us a previously overlooked,different kind of beauty.

About the Author:

Darren Lewey is behind Creative Camera, a showcase for cross-genre work, in-depth tutorials, innovative online courses and workshops designed to take your photography to the next level.

Like This Article?

Don't Miss The Next One!

Join over 100,000 photographers of all experience levels who receive our free photography tips and articles to stay current:

Leave a Reply