I never thought I would be running around with a net desperately trying to capture butterflies and dragonflies. But that was exactly what I was doing two summers ago at the local golf course.

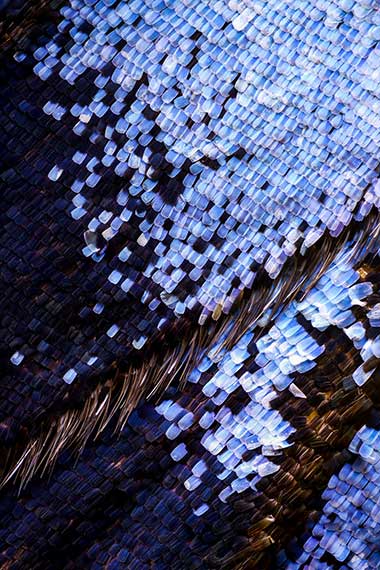

Baeotus Japetus

Living north of San Francisco I am surrounded by natural beauty with flowing waterfalls, giant redwoods, and luscious green hillsides. However, when summer comes, the waterfalls dry up and the mountains turn brown—not the most appealing subjects to photograph. To challenge myself and find natural beauty to shoot one summer, I bought a macro lens. Little did I know that this purchase would jumpstart my passion for extreme macro.

When I first began macro photography, I was stunned by all the beautiful micro worlds that we walk right by. Whenever I would go out in nature, after spending time shooting macro, I would notice the various textures on a leaf or the water drops on a spider’s web. I began to see so much more of the beauty around me and I wanted to see it even more clearly. Hence the butterfly net. I realized I needed insects that were not moving and could be lit in a studio setting. Soon my freezer was filling up with various flying insects I had captured.

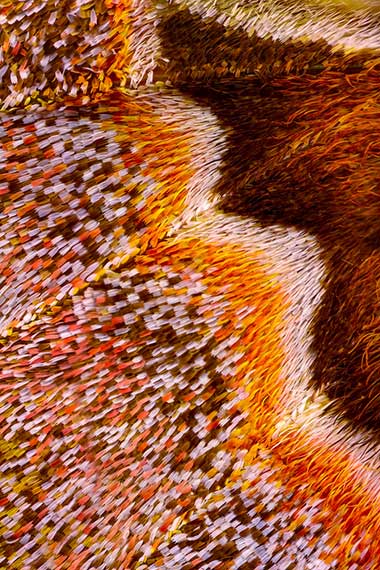

Saturn Moth Rothschildia

Now the trouble with capturing insects is that by autumn there are not too many left out there. By October any new ones I could capture were bedraggled from a long hard summer. One day discouraged with my dwindling supply of insects to photograph I went to the San Francisco Academy of Science to shoot the butterflies in their rainforest exhibit. After photographing their stunning butterflies I noticed a table full of microscopes and butterfly wings. Here I could see every detail in their wings. I knew instantly this was going to be my next project, shooting extreme macro of insects.

Researching how to take pictures with minute detail, I came across Levon Biss’s Microsculpture videos for shooting insects with microscope objectives. Acquiring a similar setup, I began to shoot insects in this new way. This was the most frustrating experience of all. The slightest mistake (a shaky table, hot lights, specks of dust, walking in the studio) and all that work would result in a blurry photo.

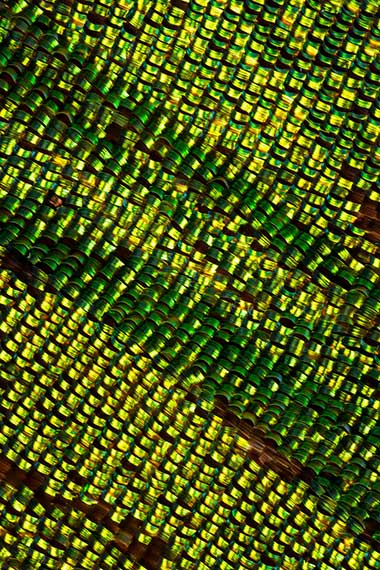

Agraulis Vanillae

The Process

The final results, though, were worth all the hard work and frustration. Each final image of a butterfly wing consists of 2,100 separate exposures merged into a single photo. So many exposures are necessary because I am using either a 10x or 5x microscope objective attached to a 200mm lens. Since the depth of field on an objective is almost nonexistent, I must go through a several step process to achieve a truly in focus shot.

Sunset Madagascar Moth

To accomplish this I use a focus rail that moves my lens no more than 3 microns (the width of a human hair is 75 microns) per photo. I then can achieve focus across the height of the subject, which can be up to 8 millimeters. This yields 350 exposures, each with a sliver in focus, that must be composited together into a single file. This file is one piece of a six piece puzzle. The process is repeated six times for different sections of the wing. The photos are then brought into Photoshop and pieced together to make a final image.

“Butterfly Wing” is my latest extreme macro project showcasing the beauty and complexity of butterflies.

About the Author

Chris Perani is an extreme macro photographer who specializes in shooting butterflies at a microscopic level.

Like This Article?

Don't Miss The Next One!

Join over 100,000 photographers of all experience levels who receive our free photography tips and articles to stay current:

Leave a Reply