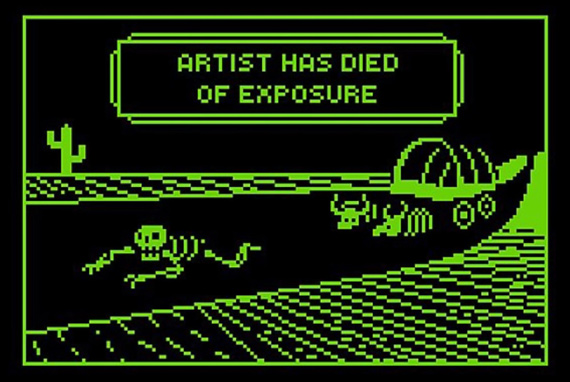

How often have you been approached to be paid in terms of “exposure”? Happens a lot, right? But exposure doesn’t put food on the table. Many professional photographers depend on the earnings they make by selling rights to their images. Recently, one of the works of concert photographer J. Salmeron was used by a company to promote themselves. And when Salmeron asked them for compensation, the band Arch Enemy ended up banning him from their concerts:

While covering the FortaRock metal festival in the Netherlands, Salmeron took an image of Alissa White-Gluz, the lead singer of Arch Enemy. When he posted the image on Instagram, it quickly grew popular.

And taking advantage of the popularity was a company called “Thunderball Clothing”. The company re-posted the image that Salmeron took with the purpose of promoting themselves. They didn’t even bother to get permission from Salmeron to use the image.

“…legally taking some else’s work and using it without permission is in principle infringing.”

The company clearly used his image for their own benefit, without the photographer getting a cut. When Salmeron approached the company to let them know that he was okay with them using the image if they agreed to donate 100 euros to the Dutch Cancer Society, he was reported to the band’s management. The band’s management told him that the sponsor had the right to use any photographer’s work taken at a show—and that he should be happy for the exposure he was getting.

“Expecting to get paid for my work was such a bad thing, such a disgusting behavior, that I shouldn’t be able to shoot concerts.”

The sad part here is how an artist from the music industry failed to understand that a photographer’s work deserved the same level of protection as theirs.

When Salmeron discussed the scenario with some high-profile music photographers, they agreed that this was terrible. What the band did by banning him was regretful, but the photographers didn’t want to risk getting banned by raising their voices against the action.

“It is certainly disappointing to see that it is a band that sells an anarchist image that has taken this approach. Maybe now that they have attained the fame and money that they so eagerly criticize in others, they fear that there isn’t enough to go around.”

What’s your take on this series of events? Do you feel that Salmeron was treated right by the band?

Like This Article?

Don't Miss The Next One!

Join over 100,000 photographers of all experience levels who receive our free photography tips and articles to stay current:

In the age of music streaming services, it’s a little ironic to me that a band’s management would want to use any photographer/artist/creator’s work for “exposure”. Musical artist are fighting to get paid for their music that is streamed and downloaded, which in essence gives them more exposure to a wider audience. It isn’t cool that they would feel it is ok to treat a fellow creative artist with less regard. And a “sponsoring” company that didn’t pay for said work definitely should not be able to benefit from this photo.

I just downloaded all her music from the Internet. Anybody interested in a cpoy? It is exposure isn’t it?

Unfortunately, there’s plenty of precedent for this. As copyright law gets more-encompassing and longer-lasting, the power falls more and more into whatever corporation is backing the most original iteration of the intellectual property. in this case, the IP of the band is overriding the “derivative work” of the photographer photographing the band.

And the situation is getting worse, not better. Used to be, if it was part of a cityscape, it was fair game. Now, you need permissions to photograph certain buildings if they’re “recognizable,” even if they’re only incidental to the composition. Same goes for cars: it’s one thing to “not look at” a corporate emblem, but a few years ago Ford declared that images showing the “C-scoop” of its Mustangs could not be used without specific release. The more pervasive corporate branding gets, the more their 800-lb gorilla lawyers abuse the protections of copyright.

What we need is some court to recognize a clear definition of “public place” and stop all these IP squatters from eating their cake and having it, too.